This Pride Month, we explore why the inclusion of LGBTQ+ populations matters in global development. In previous blogs, we discussed challenges related to inclusion, shared five things to consider when engaging LGBTQ+ populations, and challenges and opportunities for collecting LGBTQ+ data. In this blog, Jenn Williamson, vice president of gender and social inclusion at ACDI/VOCA, collaborated with Ryan Ubuntu Olson, technical advisor for health, human rights, and gender at Palladium, to identify lessons learned from the health and human rights sectors for promoting LGBTQ+ inclusion that can strengthen and inform other sectors, including agriculture and market systems development (MSD) programming.

What is a key lesson the health sector has learned about promoting the inclusion of gender and sexual minorities?

At the intersections of public health and human rights, we value the importance of knowing our epidemics and understanding systems. Using data and an intersectional lens, we bring value to the experiences of how people enter health systems. We recognize how those who are underrepresented, including gender and sexual minorities, often face the greatest health disparities and inequitable access to health services. In examining the social determinants of health, we see direct correlations between the health status of these communities and the stigma, discrimination, and violence inflicted upon them.

Bringing value to the humanity of all people by addressing not only their health needs but also the disparities they face across entire systems, including by creating enabling policy environments, helps ensure no one is left behind. Building resilience encourages people to overcome historical barriers and societal stigmas that hinder their agency and power. This has been demonstrated to improve health outcomes. While community empowerment is important, it is also important to hold accountable those who are duty-bound to protect people. This includes decision makers in government and those delivering health services. It also includes adequately training direct service providers and program partners about the rights and dignity of marginalized people and creating safe spaces where individuals feel welcomed, heard, and understood.

How could this key lesson from the health sector be incorporated into agriculture and MSD programming?

These lessons can be applied with agriculture and MSD partners, actors, and stakeholders as well as in the spaces where they work. A first step in expanding access and services to LGBTQ+ populations can and should include building partners’ capacities to create safe spaces and prevent discrimination, regardless of whether they knowingly serve or interact with gender and sexual minority groups. This means preparing partners for the existence of these groups, raising their awareness about the importance of providing equitable treatment and services, helping them ensure their procedures enable equitable access for all people, and building their capacity to engage with these groups in respectful and safe ways.

Capacity building has the potential to help a broad range of market actors — from agriculture extension agents, cooperatives, producer organizations, business development service providers, employment agencies, and chambers of commerce to investment firms and financial institutions — provide more inclusive operations and services. As discussed in part one and part two of this blog series, LGBTQ+ exclusion has significant economic costs and inhibits access to job opportunities as well as a range of services. Supporting partners and market actors to become aware of the benefits of inclusion and how to promote it will have a positive impact on the LGBTQ+ community, market systems, and society more broadly.

How can we help market actors improve their inclusion of LGBTQ+ groups?

A good example of this is INclusiónES, an initiative implemented by the Program of Alliances for Reconciliation in Colombia. This program, which is funded by USAID and implemented by ACDI/VOCA, promotes gender equity, diversity, and inclusion within private sector companies, governments, universities and schools, NGOs, civil society, and media organizations. INclusiónES seeks to equip people of different ages, genders, identities, sexual orientations, ethnic backgrounds, geographies, and abilities with contextually appropriate tools and strategies for success in their organizational environments.

Once market actors and agriculture partners improve their ability to conduct operations in safe and inclusive ways, it is beneficial to expand their capacity to collect and analyze data on the diverse populations they serve. As discussed in part three of this series, this data informs partners and implementers about who is accessing services and where there are gaps. Being able to track progress and see measurable benefits to the diverse populations they serve as well as their own bottom lines helps build a business case for promoting inclusion. However, working with partners to collect data about gender and sexual identity should only occur when a partner or stakeholder is ready to follow “do no harm” and safeguarding standards, as discussed in part two and part three of this series.

What are some key lessons learned about partnering with local LGBTQ+ organizations from the health and human rights sectors?

The health and human rights sectors recognize the importance of partnering with local LGBTQ+ organizations throughout the design and implementation of a program. The knowledge is already there; it is about identifying pathways to tap into that local knowledge and finding synergies alongside evidence-based approaches that reflect local realities.

We know that human sexuality and gender are taboo topics thanks to the remnants of colonialism. Undoing these will take time and may cause friction in ways that only local counterparts will be able to manage. Local partners understand the subtleties within a given context that can have grave ramifications for programs. Thus, ensuring local actors are part of every aspect of program design and leading implementation will ensure a greater uptake of the program’s interventions. For example, in the world of HIV, many once claimed it was too hard to find those most at risk. But when working with local communities, they found hundreds. In parallel, we must work with local groups to appropriately “see” gender and sexual minorities.

As mentioned in part two and part three of this series, it is essential to collaborate with gender and sexual minority groups to understand LGBTQ+ presence, barriers, opportunities, and risks in rural value chains and agriculture systems. For implementers interested in finding local groups to partner with, consider reaching out to organizations like OutRight Action International, Hivos, The Other Foundation, ILGA World (the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association), and APCOM to form partnerships and assist in developing those connections. Analyzing how a proposed global development program has the potential to meet the LGBTQ+ needs and not unintentionally perpetuate their exclusion requires consulting with those groups and creating feedback loops to assess change over time. Local LGBTQ+ partners should also be closely involved in developing the training and capacity building activities for and with market actors, and it is important to build entrepreneurial and commercial activities for these groups to continue to fund their human rights work.

Another important learning is that program implementers should work with local organizations to understand how gender and sexual identity is conceived and expressed in different cultures. We have used the acronym LGBTQ+ throughout this series as a term that is understood by global development professionals and readers familiar with Western culture. However, the ways gender and sexual identity are conceived, defined, and described will vary across geographies, cultures, and languages. In some areas, individuals may use terminology such as “key populations” and “LGBT,” even when English is not spoken locally because of their access to global development or advocacy initiatives.

People in rural areas or those who are less connected to global discussions on gender and sexual identity may self-define. It is important to understand local perceptions not only to ensure there are consistent definitions but also because there is power and dignity in the act of self-naming. There may be local vocabulary that gives reverence to these identities that, if tapped into from a solutions-oriented approach, can further drive inclusion. Rather than coming in from the outside, we can engage with local realities and partner to expand agency, access, and inclusion.

Why is it important to connect human and economic rights for LGBTQ+ communities?

It can be difficult for agriculture and MSD-focused programs to find common ground with LGBTQ+ advocacy organizations, though there is often a desire to work together. A gap exists that may widen on the ground due to historical differences in areas of focus and approach. However, many organizations dedicated to promoting LGBTQ+ human rights and legal protections are fully aware of how discrimination leads to negative economic impacts. In fact, OutRight Action International recently called attention to the disproportionate economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender and sexual minorities, including devastation of livelihoods and rising food insecurity.

In the health space, family planning advocates recognized that solely offering reproductive health services to people under the age of 36 — the largest demographic in history — would not account for the myriad of barriers they have to overcome to attain a dignified life. Nor could governments meet their needs without recognizing the interdependence of systems they oversee. As such, the Demographic Dividend was created to understand the impact of meeting young people’s needs in health, education, economic attainment, governance, and family planning. In countries where this framework has been adopted, societies benefit. The framework recognizes that youth have needs that should be valued outside of parallel structures or siloed interventions.

Agriculture and MSD programs understand the complex dynamics of food and agriculture systems and the restrictive social norms in rural areas that limit different groups’ access to economic opportunities. They work to make markets more inclusive, promote social norms change, and engage in transformational partnerships that shift thinking and behaviors across the entire sector. This sector is well positioned to build on these skills and bring in holistic, collaborative approaches for inclusion from the health and human rights sectors.

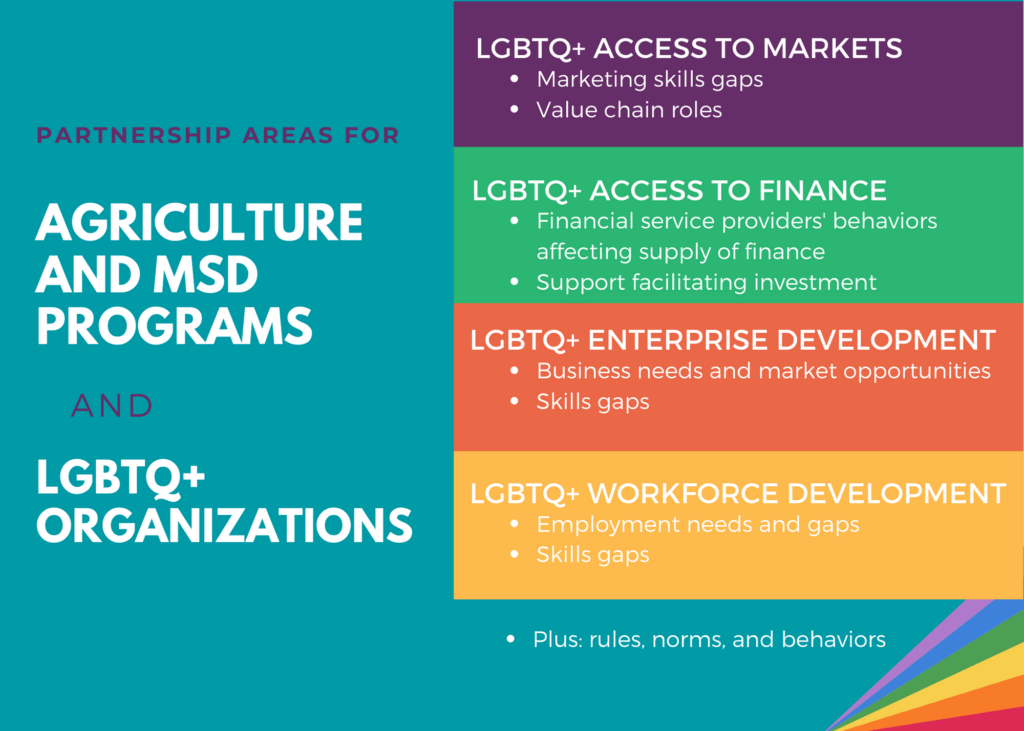

Working with local LGBTQ+ partners requires understanding how their long-term goals for equality, justice, and inclusion align with a development program’s objectives. Social and economic inclusion are mutually reinforcing goals. Just as agriculture and MSD programs target key leverage points for sparking change, many LGBTQ+ organizations devote their limited resources to areas where they see the most potential for impact. Working together enables them to leverage additional skills, resources, and attention toward excluded groups.

At the end of the day, it is critical that we see LGBTQ+ individuals holistically and in a humanistic way. While human rights frameworks give weight and meaning to one another’s lives, we also must step back and realize that we are ultimately talking about human dignity. Chloe Schwenke, founder of the Center for Values in Global Development, mentioned in a recent blog post about the effectiveness of aid that we must ultimately seek out value, worth, and a universal human dignity in all of those for whom our work is meant to serve. As we work toward agriculture and market systems that are more inclusive, sustainable, and resilient, taking a holistic, human-centered approach to inclusion will further strengthen systems and support our goals of achieving better lives for people and communities.

In case you missed it, check out the full Pride Month blog series:

- Why the Inclusion of LGBTQ+ Populations in Agriculture and Market Systems Matters, Part 1 and Part 2

- Q&A: Experts Discuss Challenges and Opportunities for Collecting LGBTQ+ Data