When I was nine years old, my uncle gave me a calf. At least, I thought he did. It happened during my family’s annual visit to my aunt and uncle’s dairy farm. For a week that summer, my brothers and I got up at dawn to help our cousins with their chores, feeding the pigs, milking the cows, and sneaking cups of cold, creamy milk from massive storage containers.

I had fallen in love with one Jersey calf, a doe-eyed girl named Penny, who loved head scratches. After watching me spend so much time with her, my uncle said Penny was mine and gave me full responsibility of taking care of her—at least for the rest of my visit. I was thrilled and fully intended to bring Penny home with me, as soon as I got my parents’ permission.

Sadly, for me, my parents never agreed to it, and when we returned the following year, Penny was gone—my uncle had sold her! I realized Penny was not actually mine. I was a heartbroken at the time, but my uncle had made a business decision for his family, and I had to understand that I—as a young girl—couldn’t reasonably own and raise a cow by myself in my parents’ backyard. As an adult, I’m amused by that childish dream. The experience taught me an important life lesson, but the question of who owns a cow matters greatly to girls and women around the world.

Livestock is an asset to many families and is the primary livelihood of many rural communities. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimates that “752 million of the world’s poor keep livestock to produce food, generate income, manage risks and build up assets.” For many families, livestock equals wealth. These animals are like savings accounts because you can sell them for cash. Families can acquire animals to grow their assets and often enhance their social status in the process.

Livestock can also be important for good nutrition. Cows and goats provide milk, butter, and yogurt, which supplement diets, especially where food is scarce. Meat provides protein and other nutrients, but is not always affordable on a regular basis for families in developing countries.

So, why does this matter to girls and women? It matters because gender roles and cultural traditions determine who can own livestock, including which types, and who does the work to care for them. For example, in some communities, men own and care for cows, but women own poultry. In others, men own cows, but women milk them and sell the extra milk their families don’t consume.

Livestock presents an opportunity for women to build assets, but control over those assets may still not belong to them. Even when women own poultry, meaning they care for chickens as part of their daily work, men often decide what veterinary medicines to buy, whether to sell the poultry, and how to spend the earnings.

ACDI/VOCA recently implemented the five-year Resiliency through Wealth, Agriculture, and Nutrition (RWANU) project, funded by USAID’s Office of Food for Peace. RWANU focused on reducing food insecurity among vulnerable populations in Uganda’s southern Karamoja region. The project achieved this by improving availability and access to food and reducing malnutrition in pregnant and lactating mothers and children under the age of five.

For centuries, pastoral communities in this region lived as nomadic herders until conflict and drought forced them to rely more on agriculture. But livestock remains vital to their survival. Traditionally, men in the region own livestock, and this ownership trickles down into other parts of their lives, like being in control of the family’s wealth and making decisions for households and communities. However, studies have shown that nutritional and social benefits occur when women own livestock.

RWANU provided goats to women’s groups to increase mothers’ and their children’s access to milk for better nutrition. Because local women did not typically own goats, ACDI/VOCA worked with community leaders and men to help them understand why women needed access to this resource. RWANU also trained women in how to care for their goats and linked them to necessary support services, like animal health workers.

So, what happened? Women who received goats through RWANU reported that their families and young children drank milk more frequently, and that they used butter and yogurt in their cooking more regularly.

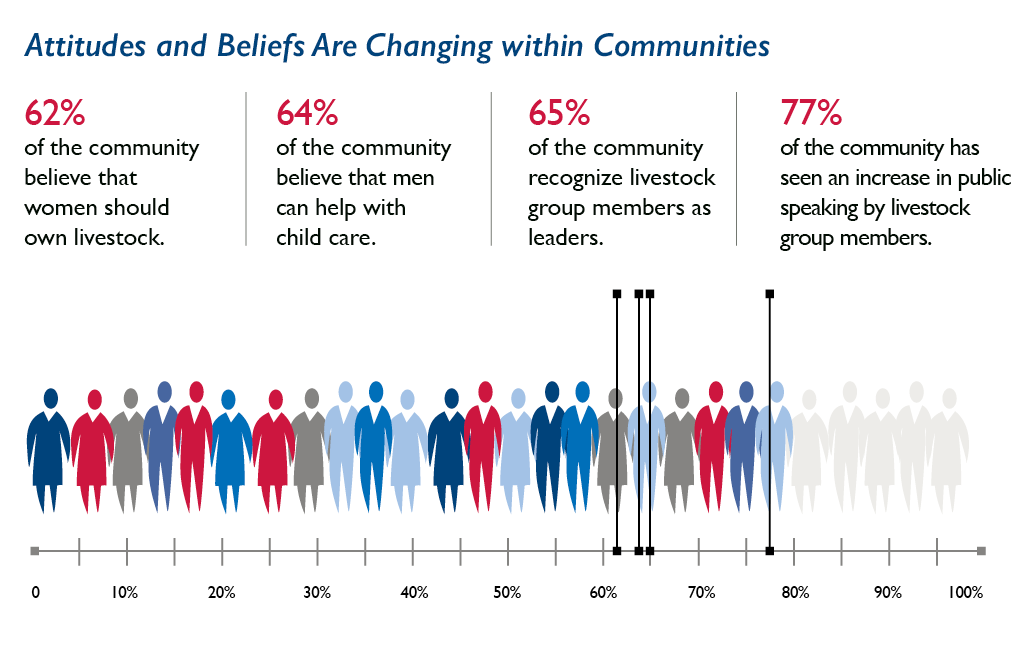

More surprisingly, women’s social statuses improved within their families and communities. As RWANU worked with community leaders and men to change their beliefs around gender and who can own livestock, the project allowed them to reflect on their attitudes and perceptions. Because women now had assets—and confidence from their newfound knowledge and skills—they earned more respect.

These findings do more than simply show how women owning livestock leads to improved nutrition and livelihoods. They also show that projects like RWANU can empower women and promote gender equality by engaging all members of a community toward positive change.

To learn more, read a short summary of ACDI/VOCA’s Livestock Activity Gender Impact Assessment in Uganda, or download the full report.

Comments